Elections (online campaigns and disinformation)

Rosa M. Navarrete, University of Mannheim

Elections in times of online campaigns and disinformation

With the Bundestag elections just around the corner, there is a growing concern about the role internet and social media platforms will play. As a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic and due to the measures taken to contain the spread of the virus, parties and candidates draw upon online communication as a way to engage with citizens and mobilize voters when mass events and meetings are not allowed. Despite the usefulness of social media as a tool to share campaign messages and enhance political discussion, most citizens are worried about electoral results and political polarization being affected by disinformation and the increasing relevance of online communication.

Experts have been analyzing the effect of social media and online news platforms on politics but they seem to disagree on whether the internet has more benefits than risks for politics. Thanks to the internet, more people have cheap access to political information and have the opportunity to compare diverse points of view because their sources are no longer restricted to their traditional newspaper, news channel, or group of friends and acquaintances. Similarly, platforms such as Twitter or Facebook allow a direct communication between citizens and their political representatives, and facilitates political discussions which is an important source of political information. At this respect, social media gives an opportunity to listen to diverse political discussion (Brundidge 2010) which could contribute to have a more complete picture of the different political options. Nevertheless, several scholars have pointed to the negative effects of the use of the internet in politics. In short, online political discussion is considered to be more ideologically homogeneous (Theocharis et al. 2016), while online political participation is associated with polarization (Grönlund et al. 2015), political intolerance (Nir 2017), and extremism (Engesser et al., 2017). Even more, the disinformation campaigns promoted by some governments such as Russia, the use of chatbots and deepfakes not only disrupt the online discussion, they also try to manipulate reality.

Most of the distrust towards online and social media lies in disinformation. Without a gatekeeper controlling and selecting which news appear on the headlines, outsiders have more chances to spread their views and share information that does not reach traditional media. This means that other political profiles can attract the interest of citizens even when they do not have the favour of their party’s elite. One well-known example of this could be Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez who ran a campaign mostly on social media and was able to beat one of the most relevant figures of the Democratic party in primary elections. However, the absence of a gatekeeper also represents an opportunity for those whose radical discourse has no space in the traditional media and for those who can benefit from spreading false information. In this respect, when something goes viral on the internet is very difficult to keep the original source accountable and, for this reason, there are no consequences for those purposely sharing false information. Regarding this, radical parties have made good use of social media to spread messages that contribute to undermine the confidence on mainstream parties and traditional media. Nationalistic and anti-immigrant rhetoric is more easily shared through social media as well as conspiracy theories that sometimes intend to disrupt the democratic order (Bennett and Livingstone 2018). The events of January 2021 with a mob trying to assault the US Capitol are just a recent example of how disinformation campaign could be used to undermine institutional legitimacy. In Europe, the Brexit campaign in which social media played a relevant role is also a prominent example of how disinformation can even change the political future of a country.

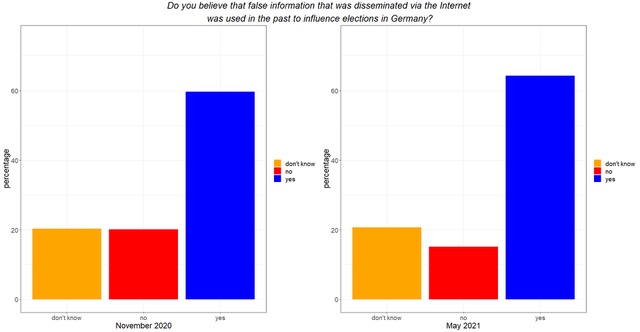

In the case of Germany, most citizens express their concern about how false information shared in social media will affect the next elections. As part of the project “digilog @ bw—Dynamics of Participation in the Era of Digitalisation” we run a panel survey, that already has two waves, in which we asked respondents whether they think that false information spread via the internet would be used to influence the federal election in Germany. In November 2020 a bit less than 60 per cent of the participants answered affirmatively, 20 per cent rejected that possibility and the remaining 20 per cent did not know. In May 2021 the percentage of those who did not know remained stable but those who believed that false information disseminated online would be used to affect the election results increased by five points, while those more sceptical about this possibility decreased to a mere 15 per cent. More into details, 37 per cent of those asked in November 2020 and 48 percent of the respondents in May 2021 feared that foreign governments will try to interfere in the elections using the internet and disinformation, and in both waves around 90 per cent of respondents pointed to Russia as the most likely foreign government with interest in disrupting the electoral campaign. Nevertheless, foreign governments are not the main concern of German citizens because in both waves more than 75 per cent of respondents who mentioned that false information via the internet will be used to influence in the elections answered that extremist groups would be responsible for the disinformation campaign. These data could be interpreted in two ways. On the one hand, it is clear that citizens in Germany are aware of how the internet is a tool that can be used to broadcast information that can have a disruptive impact on national politics. On the other, this might show that citizens are mostly sceptical about the news shared with them via the internet and, consequently, are less vulnerable than thought to disinformation. In fact, according to our survey, 80 per cent of the respondents believe that false information can be used to manipulate the public opinion and only 26 per cent of the sample said that you can trust most of the information you read on the internet. Besides, only a minority of citizens declared their main source of political information was social media and most of them trust in mainstream media as a source of political news. Therefore, citizens do not ignore the threat disinformation and radical speeches disseminated via the internet pose to democracy.

Then, do online disinformation campaigns actually work? They do, according to some of the above-mentioned facts. However, recent evidence suggests that personality traits determine whether someone engages more or less in online political discussion (Boulianne and Koc-Michalska 2021). Similarly, the preliminary analysis of the two waves of our panel survey indicates that other characteristics such as distrust towards mainstream media have a higher impact on political attitudes and vote for extremist parties than the mere use of social media and the internet. This means that some citizens will be more prone to believe conspiracies and hoaxes than others and this trait will affect their political views no matter the extent to which they use the internet to get political information.

In sum, the internet and, more specifically, social media platforms can be easily used to spread disruptive content but the extent to which they affect actual politics might be determined by how well-informed citizens are about the risks of disinformation and their willingness to believe those messages.

As already mentioned, traditional mass media used to play the role of a gatekeeper by selecting the news that would make it to the headlines. The emergence of online newspapers and magazines and the success of social media sites were first understood as an opportunity to democratize the access to information because citizens with limited resources could easily get it from different channels without investing many resources. The problem is that the responsibility of spreading false or inexact information became more diffuse. While online newspapers might have similar pressures that traditional media to provide accurate information, misinformation, and viral hoaxes are often shared via social media platforms that are not liable for what their users post. Nevertheless, these platforms have been proved to be non-independent actors. The posts appearing in a Facebook’s News Feed, a Twitter timeline or the suggestions made by Youtube pursue users’ engagement and seek their reaction (a like, a comment, a retweet…). In this pursuit of engagement, these platforms often prime messages or videos that are controversial, disruptive, and polarizing. Moreover, the original source is not always clear and bots acting as legitimate users can disturb the public discussion and broadcast hoaxes that are susceptible to become viral. Furthermore, citizens respond more to negative news and perceptions (Burden and Wichowsky 2014) so most times the most shared content, especially concerning politics, is the one that produces a negative reaction in the individual. Hence, governments’ concern about the polarizing effects of using social media to get political information and the growing interests in preventing the activities of foreign agencies and bots’ farms in these sites are perfectly understandable. But, what can be done to prevent the pernicious effects of the spread of misinformation in social media?

Some of these platforms, fearing being legally liable, implemented quality checks to inform users about the lack of accuracy of the shared content. Regarding this, the most prominent case is when Twitter added a warning label fact-checking Donald Trump’s claims about mail-in ballots and, after the events of January 6, suspended permanently Trump’s account “due to the risk of further incitement of violence"1. In that case, the ban of such a relevant public figure intensified the debate on what social media platforms could do to prevent the spread of false information and hate speech. Despite some efforts to improve the quality of the content by boosting tools to denounce false users and worrying content, Facebook and Twitter did not find a way to balance freedom of speech and true information. With more than 6000 tweets and almost 55000 Facebook posts published every second, the task of gatekeeping users’ activity is almost unmanageable.

The problem also lies in how some false information is also shared in platforms that are not open to everybody. Thus, if someone shares inaccurate content via Whatsapp very little can be done in this private interaction. Whatsapp tried to limit the number of contacts that can receive the same message at the same time, but this was just a way to make more difficult the virality of some messages but it did not totally prevent it.

For all this, the path to mitigate the effects of misinformation is two-fold. On the one hand, online news platforms and social media sites should implement measures to prevent the spread of fake news. In this job, the use of artificial intelligence can help them identify the most incendiary messages or fake accounts that act to interfere in politics. Similarly, paid content that appears as advertisements or sponsored messages should also be checked so foreign agencies and extremist groups do not succeed in manipulating citizens’ preferences. On the other hand, the promotion of trustful institutions that check the quality of the information could also help citizens to identify which sources are more reliable. As Google’s Fact-Check tool, other sites could be useful to provide citizens with accurate information to disprove hoaxes.

Nevertheless, attending to our survey data, German citizens seem to be very aware of the dangers and problems of online information. Moreover, the experience of the USA has contributed also to alert citizens about the risks of sharing inaccurate claims of electoral fraud. Consequently, the current influence of misinformation and fake news on electoral behaviour in Germany seems negligible. This brings hope because individuals are more difficult to manipulate if they understand the potential and limitations of online content. Thus, the most useful way to battle against misinformation is by educating people on the benefits and risks of social media. If citizens know how to double-check what they read on social media and understand which sources are more reliable, the disruptive power of misinformation in social media will be clearly attenuated.

1https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/company/2020/suspension

References

Bennett, W. L. and Livingston, S. (2018) ‘The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions’, European Journal of Communication, 33(2), pp. 122–139. doi: 10.1177/0267323118760317.

Boulianne, S. and Koc-Michalska, K. (2021) ‘The Role of Personality in Political Talk and Like-Minded Discussion’, The International Journal of Press/Politics. doi: 10.1177/1940161221994096.

Brundidge, J. (2010) ‘Political Discussion and News use in the Contemporary Public Sphere: The Accessibility and Traversability of the Internet’, Javnost-the Public 17 (2): 63–81

Burden, Barry C., and Wichowsky, A. (2014). ‘Economic Discontent as a Mobilizer: Unemployment and Voter Turnout.’ Journal of Politics 76(4).

Engesser, S., Ernst, N., Esser, F. and Büchel, F. (2017) ‘Populism and social media: how politicians spread a fragmented ideology’, Information, Communication & Society, 20:8, 1109-1126, DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2016.1207697

Grönlund, K., Herne, K., and Setala, M. (2015) ‘Does Enclave Deliberation Polarize Opinions?’ Political Behavior 37 (4): 995–1020. doi:10.1007/s11109-015-9304-x.

Nir, L. (2017) ‘Disagreement in Political Discussion.’ In The Oxford Handbook of Political Communication, eds. Kenski, Kate, Jamieson, Kathleen Hall. New York: Oxford University Press.

Theocharis, Y., Barberá, P., Fazekas, Z., Popa, S.A. and Parnet, O. (2016), A Bad Workman Blames His Tweets: The Consequences of Citizens' Uncivil Twitter Use When Interacting With Party Candidates. Journal of Communication, 66: 1007-1031. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12259